So I’m going to start off-topic and go back to a question that I faced when I was deciding whether to do an MBA; why do an MBA in the first place? For me, one of the big reasons was that what I was doing in my job role wasn’t really what I studied. That will be a problem for some people (like me) who feel like if they aren’t formally trained in the area, they don’t really have a handle on what’s going on. For other people, picking it up on the job is fine so one of the first things to ask is which one are you? One of the big things an MBA can offer is an introduction to and basic proficiency with a range of management functions that you need to be effective. One of the areas that I felt my technical degree really didn’t prepare me for was managing people.

For the first few years after you graduate your role as an engineer is mostly technical, you draft, you go to internal planning meetings and design reviews and as your competence grows you get your own piece of the project to work with, first as a designer with drafting support then taking on more and more responsibility until you’re the lead engineer doing process and conceptual stuff, general assemblies and layouts and supporting the team of designers under you. This transition is gradual and takes place over a decade or more (your mileage may vary) but all of a sudden your in your 30’s and you’re no longer “engineering”, instead you’re managing an engineering team.

There are a lot of things that go into being a good manager of a technical team and I’ve been fortunate enough to work under some really good technical managers. Which is a really interesting thing to say because what makes a “good” technical manager? This was one of the things that I puzzled over pre-MBA, I could identify specific instances where they handled things really well or behaviors that were really effective but I had no idea how they all tied together. For example, one manager was always able to deliver on-time regardless of the resources he was given (although that did impact quality). Watching him work, he’d do a lap in the morning, sit at each team members desk for a couple of minutes (took about an hour and a half which meant he got the early ones early and the late ones when they came in too) and asked about tasks for the day and if there were any roadblocks, when he’d get out of the way. You didn’t see him until lunchtime, he worked in his office which was at the entrance to the teams work area and anyone from outside the team, wandering down the hall, got called into his office.

The reason it was so effective was because he understood what motivated those guys, they wanted to do a good job and being engineers and designers, they needed a couple of solid, uninterrupted hours to get into it. He asked his guys what they needed, then went and (to the best of his ability) did it. Meanwhile he ran interference, both up the ladder protecting the guys from other division that would poach and down the ladder from those one-thousand-and-one little attention grabbers that crop up during the day. His teams productivity was higher than anyone else’s in the company, by a lot. Engineers fought to get in his team so he got the best talent and it became a self reinforcing cycle.

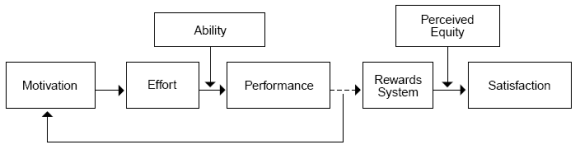

The moral of the story here is pretty clear but when I was watching, the cause and effect was as far as I got, once I got into the MBA I understood that it ran deeper that that, the insight being that he understood what motivated his guys. Some of them wanted to do their best because the environment he created allowed them to get their best work done, some saw a winning team and wanted a piece, some appreciated being left alone to do what they knew needed to be done but the common thread was that he understood what motivated all of them and gave it to them. During the MBA I came across this model which was developed by Vroom and expanded on by Porter and Lawler (called the expectancy theory model) explaining how feedback on performance via the rewards system drives motivation.

A lot of time we see the word reward and we think compensation but it’s so much more than that. When you’ve got to turn up to work every day for the next 40 years, having somewhere you can turn up to and have a working environment you enjoy vs. having a working environment that causes you to develop a nervous twitch is worth a lot of money. This notion of extrinsic and intrinsic rewards also has to be equitable. When I compare my rewards with others I need to feel good about them, otherwise I don’t value them. In the same vein, Lawler and Porter did some pretty interesting research around how we value rewards and when a reward isn’t a reward. eg: a $20k bonus doesn’t mean as much to the CEO as it does to a drafty in fact it might demotivate a CEO because they look around and see the other people at their level getting a whole lot more in terms of bonus.

Having a framework like this is really useful for someone like me. When I’m looking at a teams performance I can use a model like the one above to analyze the components that can be tweaked to increase performance. When you want to be good at something you practice, you learn about it and you try and improve what you’re doing. An MBA is one way to do this, it helps you organize your management strategies and apply a system to what you do. If you’re struggling because your current job role has migrated from technical to managerial ask yourself whether that’s what you want, if it is then maybe an MBA can help.