One of the first units that MBS runs is a subject on decision making. By putting this early in the course, MBS tries to help students come to grip with making hard decisions which is something that you have to do regularly. Whether it’s deciding which bits of material are the most relevant to a decision (I’m convinced that one of the aims of the MBA core is to give people far more information than they can process so they have to develop the skill of quickly assessing a lot of information to find what they absolutely need) or figuring out which discussion tactic to use in a class to convince the room that there’s another side to an issue, exploring what drives the decision making process is essential.

So what makes a decision “hard” to make? The general consensus is when it involves one or more of the following:

- Complexity: this can be obviously complex problems such as which school should I go to or subtly complex problems such as should I raise a contentious point in the classroom? As an engineer, I often find myself doing a lot of scenario modeling and assessment of ripple effects to try and handle this, even if it’s only a couple of seconds worth, because it’s the way I have been trained to think about problems

- Inherent Uncertainty: this can be risks that you know are present, but you aren’t sure how they will turn out (which way a coin will land when flipped) but could also be risks you had no idea you were taking (someone was flipping a coin?!?)

- Balancing Trade-offs: not so bad when you can quantify the value of the items being traded off. Much more difficult when you are trading off things that are hard to quantify (time spend with a partner vs. putting in extra time on an assignment) or when they are measured in different ways (time spent with your partner vs. the extra pay you get for doing overtime)

- Different Perspectives: this one was especially difficult for me because at times I struggle to see other peoples points of view, particularly when they are driven out of culture or experience that I haven’t shared. This has lead to one of my key learnings during the MBA, the value of diversity. Diversity isn’t just a buzzword, there’s real value to be had where people bring different viewpoints to the table but more on that in another post…

In addition to this, there are a couple more things that I think influence the decision making process. One is time: if you are under time pressure then the chances of one of those other risk factors above is more likely to cause you to make a bad decision. The other is whether you’ve seen the problem before: this is a bit of a double edged sword really. As humans, we develop habits or patterns of response to shortcut the decision making process. This is generally a good thing (we’d be paralyzed by choice otherwise) but the problem is that sometimes we get into a habit and then things change but the habit doesn’t (I’m thinking of my late-night studying 2 minute noodle addiction which was fine during undergrad when I had the metabolism of a 20 year old but during the MBA, is just making me fat!). Along side this habitual response is the idea of assumed knowledge, the fact that you are familiar with something doesn’t actually necessarily mean you are better equipped to make a decision about it which might not make a lot of sense but bear with me and I’ll give you an example.

The current dean of the Melbourne Business School, Zeger Degraeve is a professor in his own right and his primary area of expertise is risk and quality decision making (how to make good decisions). We were lucky enough to have him come in and give a two hour guest lecture and during that time, he ran an experiment to help make his point. He got a thumbtack (just a regular one, no tricky stuff) and a cup and saucer, put the thumbtack in the cup and then placed the cup upside down (with the thumbtack underneath) on the saucer. Then he shook it and asked one of the class members to make a guess: was the tack sitting on it’s flat top (with the point sticking in the air) or was it sitting on its side (with the point and the edge of the tack both touching the saucer). The reason that Zeger uses a thumbtack is because although it looks like a simple problem, in fact it’s complex (due to the uncertainty as per this previous discussion). But we all recognize a thumbtack, we’ve used them a thousand times before but despite all that knowledge we have no idea what the likelihood is of a thumbtack ending up pin up or pin down. So how do we make a decision?

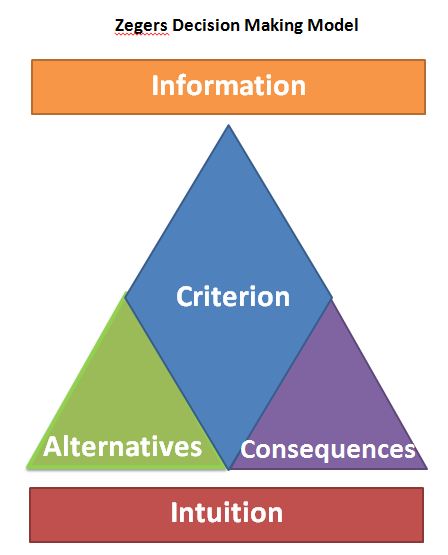

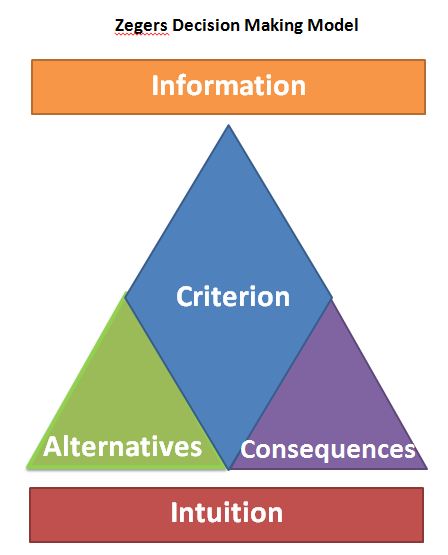

At this point Zeger introduced a framework that we could use to help to sort through the information called ICACI

- Information – What do I know

- Criterion – What am I trying to get out of this decision

- Alternatives – What Choices do I have?

- Consequences – What are the possible outcomes of each alternatives

- Intuition – What do I feel. Do I trust this?

So we worked through the model and tried to apply logic (we tried a couple of simulations and then discussed the likelihood of pin up vs. pin down) but we still didn’t have anything that allowed us to make a better decision than when we first looked at the problem. But now the class felt like we were failing at decision making because the we’d just agreed that the most important part of being a decision maker is that if you are the responsible person, you have to understand what the likelihood of failure is and here we were making a decision based on no data, just intuition. So we moved on to trying to understand what the consequences were for being wrong (in this case, a student had made a $50 bet with Zeger about whether they’d be right or not) which meant that the decision makers job is not just to work out the likelihood of failure but also to work out if you can stand the pain if the decision is wrong and accept responsibility for the consequences.

This lead to the last lesson of the day: managing to results causes crises. If you look only at the result then you ignore decision quality and consistently good decision making gives the best chance of success. This was demonstrated when we eventually looked under the cup. The student had picked pin up as their decision as to which way the thumbtack was sitting but when the cup was raised, the pin was on it’s side. There was a general air of disappointment around the classroom but Zeger took us back to the model. We’d done everything we could to make a good decision and in the end, our decision was wrong. The fault wasn’t with the process (we couldn’t have done anything better and given those circumstances, no-one could’ve made a better choice) and so if we judge the decision based on the outcome we’ll end up punishing someone for the wrong thing.

This was really salient because when you think about it, a lot of the things we do in at work are judged based on the results, not on the way we get to the results. Someone can get lucky (or unlucky) and get a good (or bad) outcome but if we want repeatability then it’s the process that matters, and that’s what you should be judging people on.