- Complexity: this can be obviously complex problems such as which school should I go to or subtly complex problems such as should I raise a contentious point in the classroom? As an engineer, I often find myself doing a lot of scenario modeling and assessment of ripple effects to try and handle this, even if it’s only a couple of seconds worth, because it’s the way I have been trained to think about problems

- Inherent Uncertainty: this can be risks that you know are present, but you aren’t sure how they will turn out (which way a coin will land when flipped) but could also be risks you had no idea you were taking (someone was flipping a coin?!?)

- Balancing Trade-offs: not so bad when you can quantify the value of the items being traded off. Much more difficult when you are trading off things that are hard to quantify (time spend with a partner vs. putting in extra time on an assignment) or when they are measured in different ways (time spent with your partner vs. the extra pay you get for doing overtime)

- Different Perspectives: this one was especially difficult for me because at times I struggle to see other peoples points of view, particularly when they are driven out of culture or experience that I haven’t shared. This has lead to one of my key learnings during the MBA, the value of diversity. Diversity isn’t just a buzzword, there’s real value to be had where people bring different viewpoints to the table but more on that in another post…

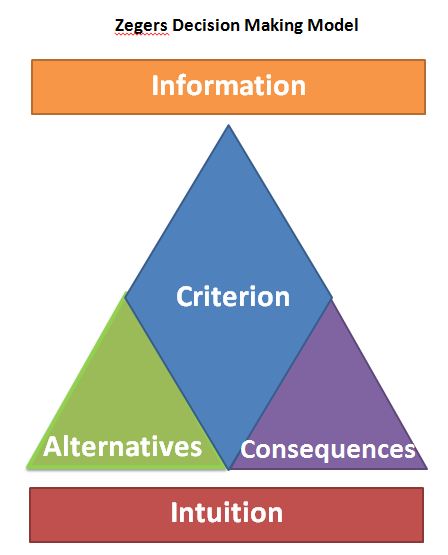

- Information – What do I know

- Criterion – What am I trying to get out of this decision

- Alternatives – What Choices do I have?

- Consequences – What are the possible outcomes of each alternatives

- Intuition – What do I feel. Do I trust this?

So we worked through the model and tried to apply logic (we tried a couple of simulations and then discussed the likelihood of pin up vs. pin down) but we still didn’t have anything that allowed us to make a better decision than when we first looked at the problem. But now the class felt like we were failing at decision making because the we’d just agreed that the most important part of being a decision maker is that if you are the responsible person, you have to understand what the likelihood of failure is and here we were making a decision based on no data, just intuition. So we moved on to trying to understand what the consequences were for being wrong (in this case, a student had made a $50 bet with Zeger about whether they’d be right or not) which meant that the decision makers job is not just to work out the likelihood of failure but also to work out if you can stand the pain if the decision is wrong and accept responsibility for the consequences.